The weird land we call New Jersey has gone through many changes over the past billion years. Ginormous volcanic arcs collided into it. It was once connected to Africa. Volcanic activity created the Watchung Mountains and Palisades cliffs. The southern half of New Jersey was once an ocean floor (Pine Barrens). All this activity has compressed a lot of interesting geology, petrology, and paleontology into a small space. Most of the interesting mineral matter is now coated with a crust of condominiums, warehouses and Wawas, but there are still some cool rocks to roll and landmarks to explore.

New Jersey has a diatreme-style volcano in the Beemerville (or is it Libertyville) area of Wantage Township. Diatremes are different from the classic cone-shaped volcano that we made as kids using paper mache, baking soda, food coloring, and vinegar. Instead of a giant mountain erupting molten lava, diatremes are more like pipes of magma that encounter ground water, causing huge steam and stone explosions, and leaving mounds of debris. Often the debris contains diamonds. This is what the internet tells me.

Rutan Hill, New Jersey’s volcano, would be easy to miss if not for the street signs for “Volcanic Hill Road”. It is, after all, a mound of volcanic debris rather than a mountain — and like most of New Jersey it is covered with lawns and houses. It’s small. Relatively small compared to the non-volcanic Kittatinny Mountain to its west. But that’s okay. New Jersey is a small state. Jersey’s volcano should be petit as well.

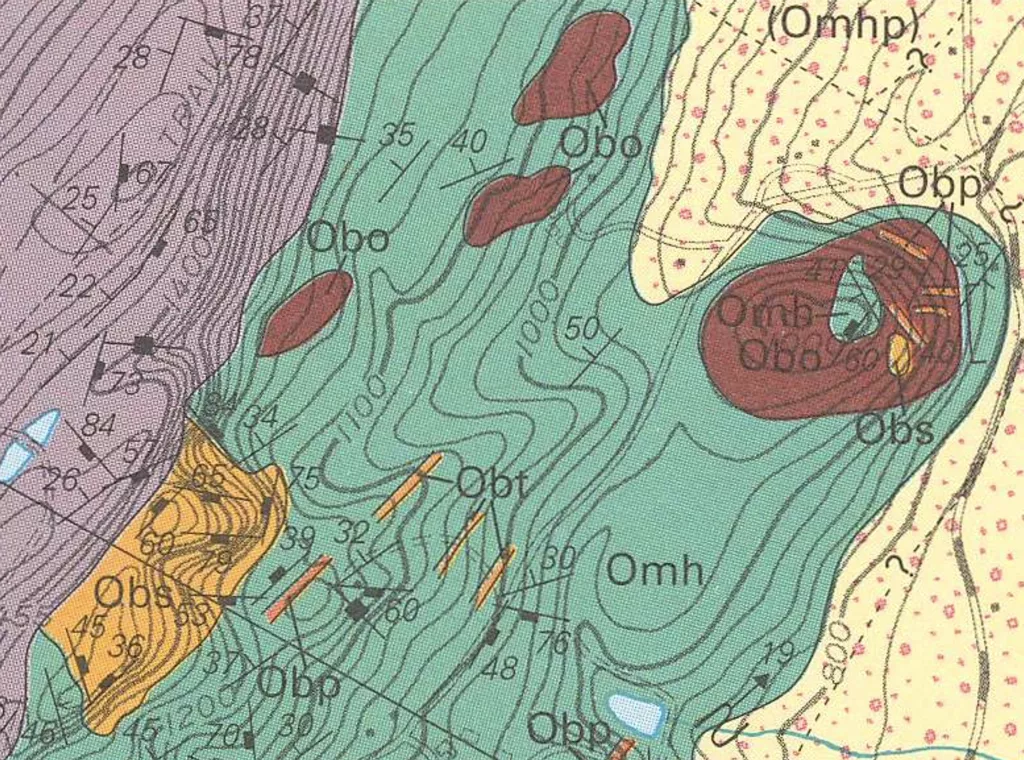

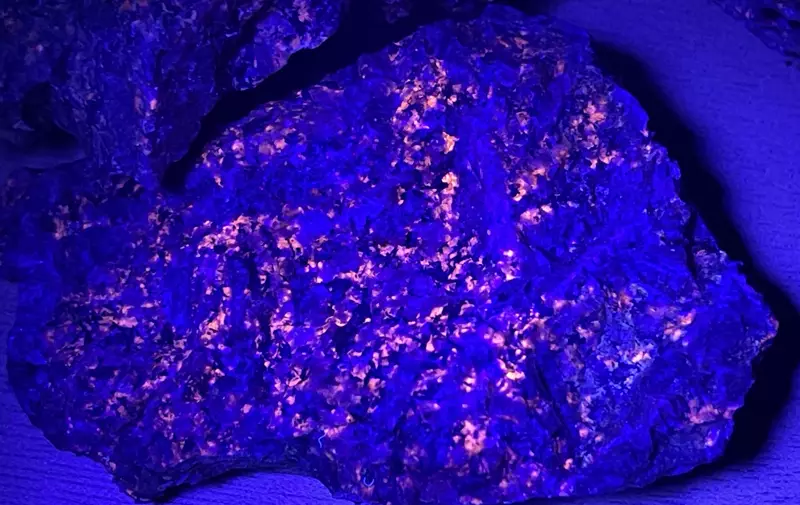

I like that Rutan Hill exists, but there are other more fascinating igneous mounds down the road and up a hill. The image below comes from Bedrock geologic map of the Branchville quadrangle, Sussex County, New Jersey a map by Drake, A.A., Jr., and Monteverde, D.H from 1992. The brown bear-paw shaped area on the right side of the map is Rutan Hill. The orange melted-cheese-block-shaped area on the left side of the image is a mass of Nepheline syenite, a relatively rare plutonic rock that formed as part of the same igneous activity as Rutan Hill. What is more interesting it the rock contains a mineral called sodalite that glows fire-orange under a long-wave blacklight!

You might have heard of the fluorescent rocks of Sterling Hill and Franklin, New Jersey, but those are different from the sodalite of Beemerville. This is the same type of fluorescent sodalite people find on the shores of Lake Superior in Michigan. In Michigan, folks call sodalite rocks Yooperlites™. In New Jersey, we can call it Beemervillite (I just made that up). The Rutan Hill diatreme, plus nearby dykes, and small igneous plutons (including the “melted cheese block”), known as the Beemerville Nepheline Syenite Complex, make up the western end of something geologists call the Cortlandt-Beemerville Magmatic Belt, which spans from Beemerville, east through New York to almost the Connecticut border.

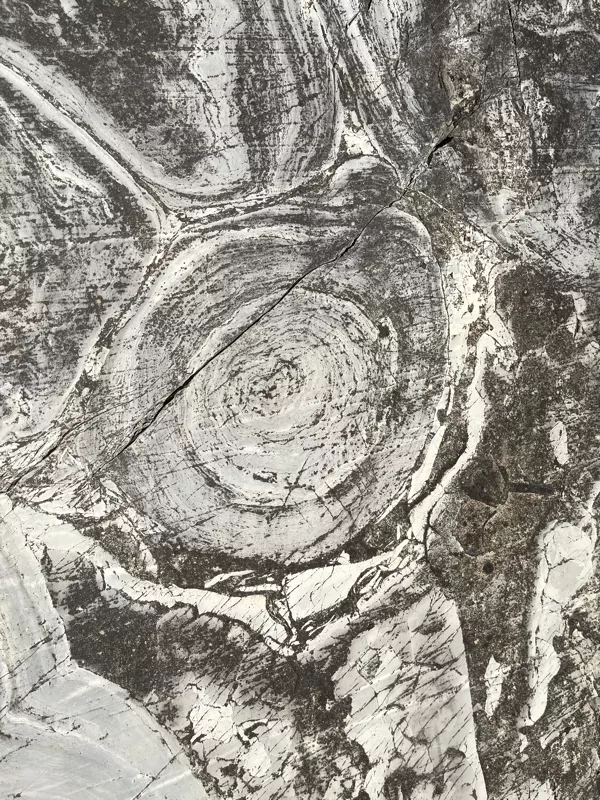

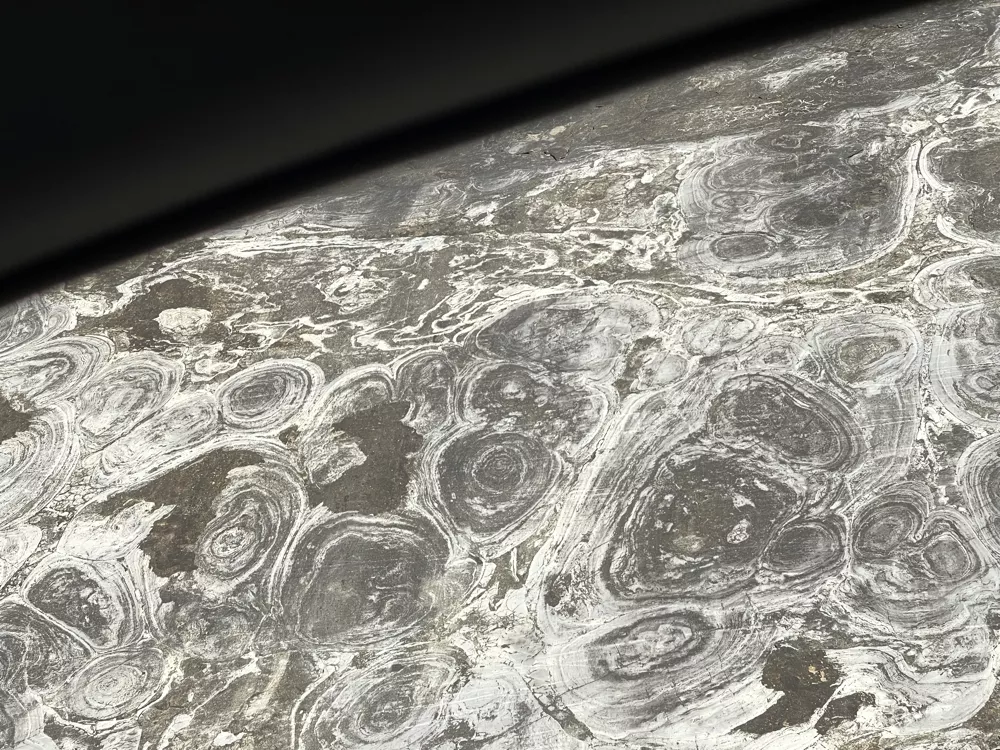

Here’s what the “melted cheese block” (aka Mount McMitchell?) looks like in person:

It looks like someone took Machu Picchu and wrecked it with a giant bulldozer, because the rocks are blocky and seemingly in random piles. Maybe someone tried to quarry the rock at one point, and left a mess. It seems like this geological feature is called Mount McMitchell from what I read on Peakery. Some people know Mount McMitchell because of a nearby plane crash!

If you want to find Mount McMitchell, park at Turner Mansion at Lusscroft Farms, and walk down the road a ways until you get to the “Shortcut Trail” aka trail O. Follow trail O until you see what looks like a huge pile of giant charcoal briquettes, and that’s Mount McMitchell or one of the Beemerville Nepheline Syenite igneous intrusions that contain the glowing rocks.

There’s a second, larger mount of Nepheline syenite south of the Mount McMitchell site as well. You can find it on the Bedrock geologic map of the Branchville quadrangle.

Of course bring a blacklight. The type you want is the long-wave type, which is fortunately cheaper than the short-wave type, and you can also use long-wave UV blacklights on the blacklight posters in your conversion van…

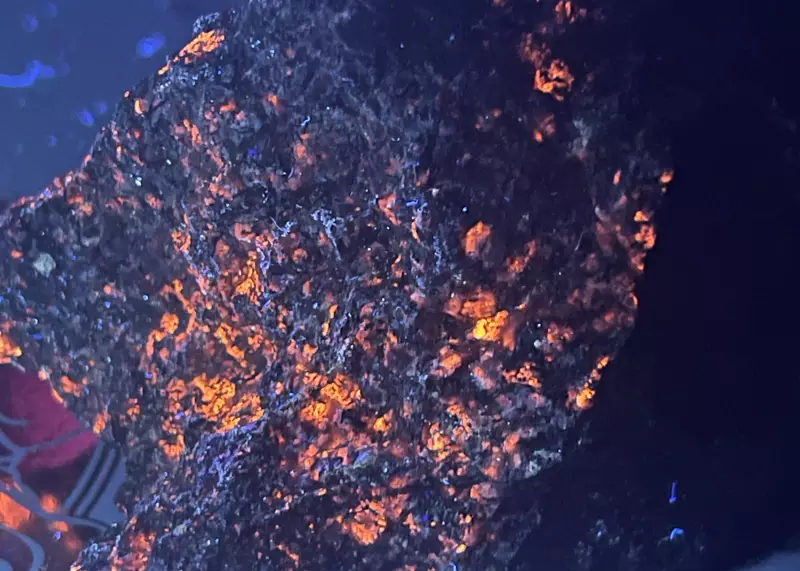

Under a long-wave UV lamp, aka “blacklight” (365nm), they the sodalite glows like hot coals:

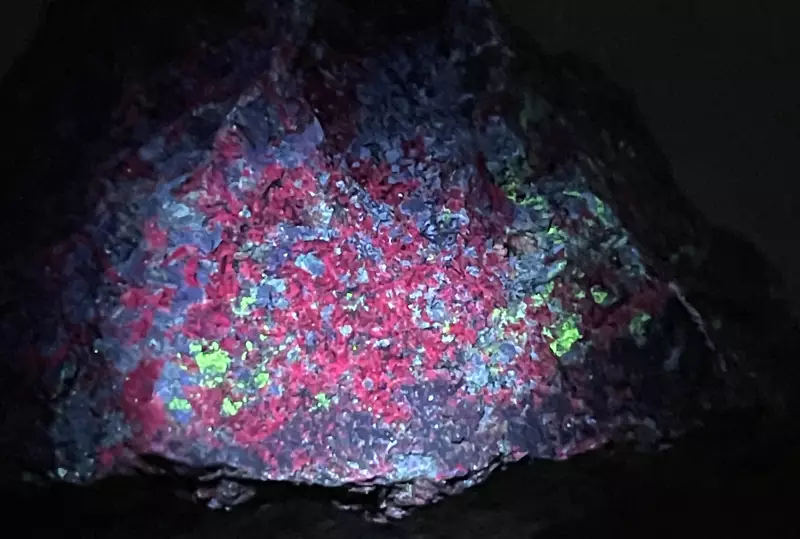

Under a short-wave UV lamp (255nm) they glow a dim cherry red, which is orthoclase feldspar, and sometimes green, which I have heard is hyalite opal or zircons.

In theory, if you bring a large enough blacklight, you can light up the mountain at night. Maybe if you scrub off the lichen and moss first.

Further reading:

- the Cortlandt-Beemerville Magmatic Belt (uml.edu)

- Nepheline syenite (usgs.com)

- Beemerville main nepheline-syenite mass, Libertyville, Wantage Township, Sussex County, New Jersey, USA (mindat.org)

- Lusscroft Farm (lusscroft.org)

- Yooperlites